The day after Ronald Reagan was elected, my eighth-grade classmates cheered and high-fived in the hallways while I gloomily loaded my knapsack into my locker.

“The rich are going to get richer, and the poor are going to get poorer,” I said to my Reagan-loving friends at lunchtime, mostly boys in polo shirts and Dockers who liked to say things like “Man is entitled to the fruits of his labor.”

We were kids, parroting the things we heard from our parents, news commentators, and teachers whose politics aligned with our own.

Thirteen-year-old me got nowhere with her friends, but she called it. Since 1980, economic inequality in the United States has skyrocketed.

This chart from Paul Krugman’s (former) New York Times blog shows what happened. As he explains: “The chart shows the share of the richest 10 percent of the American population in total income—an indicator that closely tracks many other measures of economic inequality.”

We had the Gilded Age, a time of stark inequality, followed by the mid-20th century’s Great Compression, when the divide between the rich and poor flattened and the U.S. had a strong middle class. That took a sharp turn around 1980.

Today, the country has the same level of inequality we experienced during the Gilded Age. If the big, hideous bill becomes law, it will get much worse.

Taxes aren’t the whole story, but they’re a big part of it. In 1980, the top rate was 70%; today it’s 37%.

I was not a prodigy. I was just a girl who read the paper and liked arguing with cute but politically misguided boys. You can say it was a lucky guess—I’ve been wrong about lots of other things. Honestly, though, I think I got it right because the math wasn’t hard: If you cut taxes for the wealthy, there will be fewer resources for everyone else.

When Democratic Socialist Zohran Mamdani won the primary for New York City mayor last month, I felt a profound sense of relief. Yes, I know: A primary is not a general election (though in New York City it essentially is), New York City is not the United States, and Mamdani didn’t win among the poorest New Yorkers (his victory was sealed from middle- and working-class New Yorkers; the richest and the poorest voted for Andrew Cuomo).

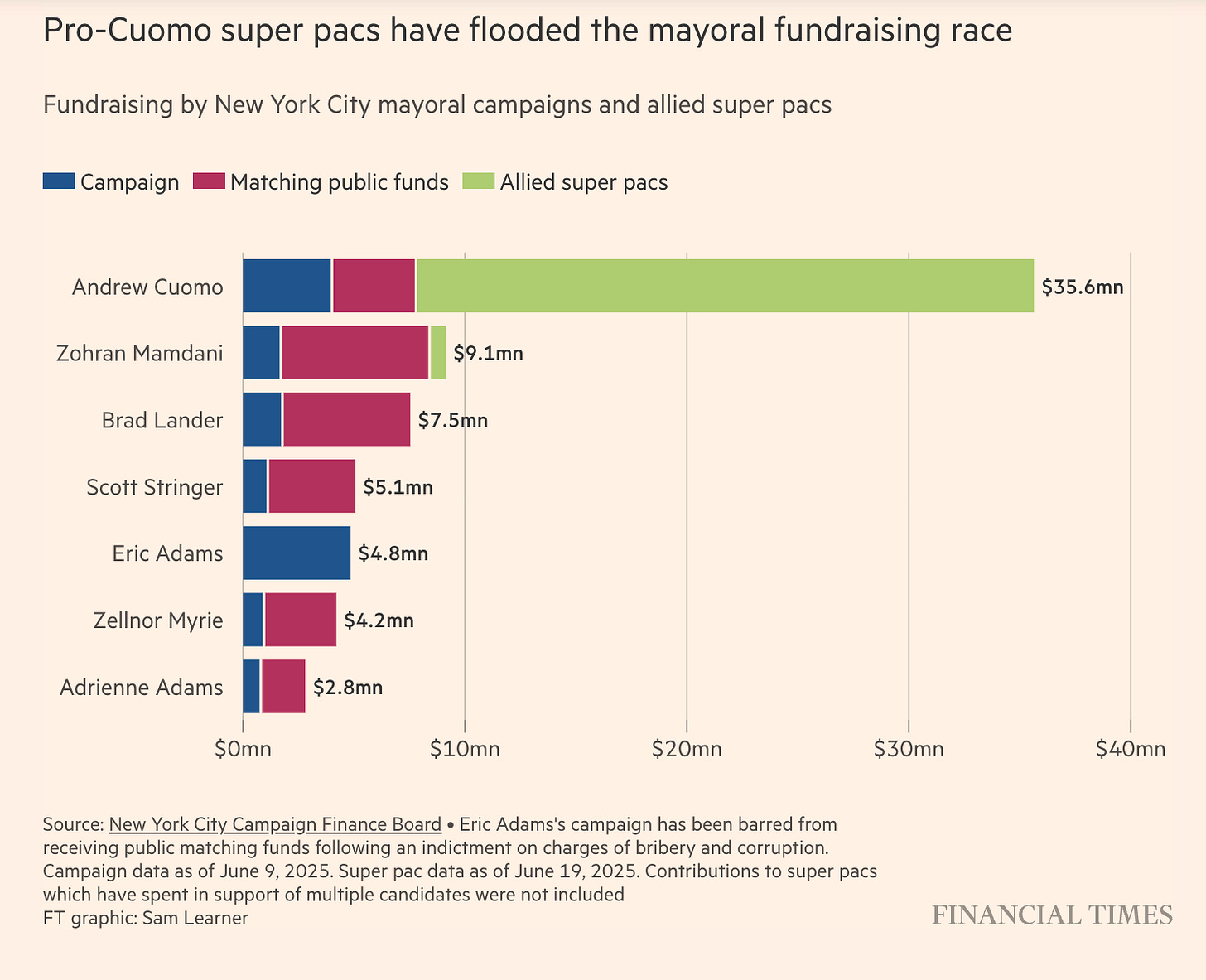

Mamdani’s victory inspires me because of what he was up against: The Democratic party establishment, a $35.6 million war chest, and the disapproval of the New York Times editorial board.

Voters didn’t care. They elected the person who said something that made sense to them. If we raise taxes on the wealthy, we can have good things: Free buses and childcare, affordable rents, cheaper groceries.

I don’t know if Mamdani’s proposals will succeed—for one, he faces stiff headwinds with Governor Kathy Hochul—but I’m excited that he’s forcing people to have this conversation.

When liberals and centrists criticize progressives, the argument is usually focused on culture-war issues like pronoun usage or defunding the police. Progressives are accused of being performative grievance mongers who harm the Democratic party by focusing on issues that alienate the average voter. (Whether they have a point or not is another essay, but these are the tropes they lean into the most.)

Mamdani’s campaign was not about the culture wars. It was about economics. And now that he has won, the liberals and centrists have to explain why they think his economic policies are bad.

Specifically, they have to explain why a 2% tax hike on New Yorkers making more than $1 million a year is a bad idea.

So far, the main argument is that the wealthy would leave New York.

Oh, no! But what will happen to all those five-bedroom Central Park West penthouses and Upper East Side triplexes? Would the city have to break those up into smaller apartments where many more families could live?

The centrist response is that even at the current rate, New York’s wealthy pay an enormous amount in taxes, and if they left the city would suffer financially.

The problem with that argument is that there’s scant evidence that a modest tax hike would prompt an exodus of millionaires and billionaires, at least according to analyses from the communists at Fortune and Forbes.

In 2019, Dutch historian Rutger Bregman became instantly famous while speaking on a panel at Davos, the annual conference where business and government leaders—rich people—convene to find solutions to the world’s problems. Bregman spoke on a panel discussing economic inequality:

I hear people talk in the language of participation and justice and equality and transparency, but then, I mean, almost no one raises the real issue of tax avoidance, right, and of the rich just not paying their fair share. I mean, it feels like I’m at a firefighter conference and no one's allowed to speak about water.

I often hear people say Democrats are stymied by their big tent. With so many different ethnicities, identities, views on Israel-Gaza, etc., it’s hard to find issues that resonate across all the different groups.

One thing nearly all of us have in common: We’re not wealthy.

Tax the rich. Three short words. Easy to fit on a hashtag, bumper sticker, lawn sign, t-shirt. And as the Republican party continues to redistribute wealth upward, it’s more salient than ever.

That’s what excites me about Mamdani—he wants to put out the economic-inequality fire with water, and if the Democratic party establishment balks, we really need to ask why.

Did you read Bregman’s books? I just finished his latest (Moral Ambition). I can recommend it and I’m thinking of what to do next. It’s one of those books that inspires action.

How about "show me the money" or "share the wealth". Or Stop taxing seniors!